One of the first lessons that each model aircraft flyer learns is that we’re dependent from the weather. Sunshine results in thermal lift or favorable wind conditions at cliffs.

Precipitation is so detrimental for most model aircraft, that it interrupts or downright cancels a flight day.

Particulary light-weight models are susceptible to wind. The lighter they are, the farther they are displaced above ground by the slightest breeze. In the very first flying lesson, we get taught: Take off and land against the wind. Tailwind and Crosswind are unfavorable or outright dangerous.

For me, Crosswind is fun!

Crosswind makes the flight day more interesting because it poses an additional challenge to my flying skills. It also prevents boredom since each time it’s somewhat different. I’d like to sketch out how to discern crosswind and how to make use of it.

What is Crosswind?

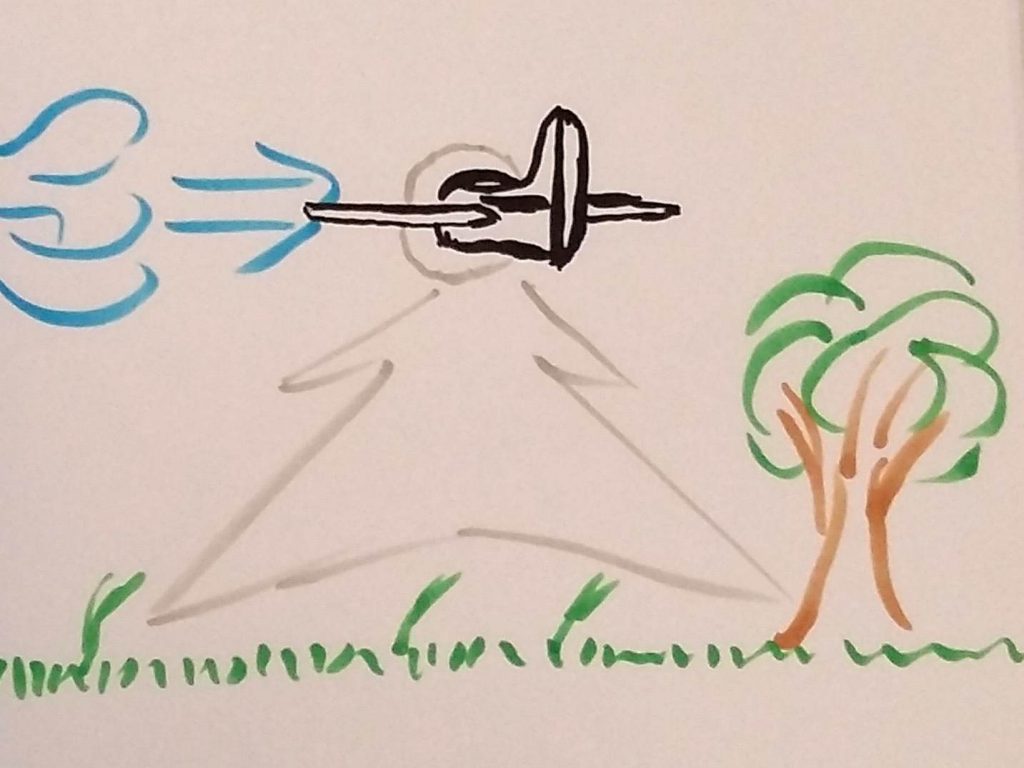

Crosswind always refers to the heading, i.e. the direction in which the aircraft moves. The wind displaces the aircraft above the ground, so it doesn’t reach it’s destination. At the same time, the aircraft’s tail acts like a weathervane and turns the aircraft’s nose into the wind.

Crosswind may blow steadily or in gusts. The latter are especially dangerous during takeoff and landing because you will have very little room for error. Takeoff and landing are normally performed against the wind. On a mowed meadow, you simply approach from the downwind side of the meadow and land with headwind. If however you want to land on a predefined runway, you might have a partial or even full crosswind. If on top of that the aircraft is caught by a gust just before touchdown, it can get ugly really fast.

How to discern crosswind?

One might think: “Studid question, that’s what I’ve got a weather app for”. True, but it will only display the next weather station’s data. In order to fly a model aircraft, we need the actual conditions at the current location and in real-time, not just between two flights.

Model airfields require windsocks. They show the wind’s direction and hint at its speed. When flying outside an airfield, you will need to observe the environment: Tall grass, branches and trails of smoke can help. The good old wetted finger is quite useful. Or you’re completely equipped and you’ve got a mobile windsock with you.

Being a model aircraft pilot you’d be well-off to making it a habit to observe your surroundings. I tend to pick a good wind indicator that I can check regularly during flight. More often than not, it’s reed grass which reacts quite sensitively to wind. Ideally, you’d have two to three such points and check the one which is windward to the aircraft. Thus you’ve got several seconds of reaction time, before any change in the wind conditions reaches the model.

What to do with crosswind?

A model aircraft pilot should have a firm grip on the model aircraft. For instance, you should be able to purposefully and repeatably fly a box above distinctive landmarks. Wind will make each leg of the box a different challenge: Headwind, crosswind, tailwind. Tail- and headwind will slow down and speed up the aircraft respectively. Crosswind will displace it. If the wind blows from an angle, it’s getting sporty.

Landing with crosswind is quite demanding, especially in gusty conditions. Since that’s a chapter in its own right, I won’t address it here.

How to counter crosswind?

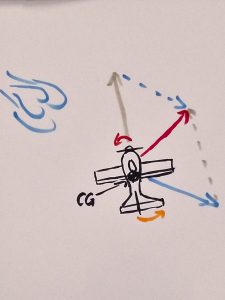

As stated above, crosswind displaces the aircraft above ground while its nose is turned into the wind. It depends on the aircraft which effect is stronger, but both are corrected by the rudder.

You counter displacement by deploying rudder into the wind: wind from the left, aircraft drifts to the right, rudder left.

If the nose is being turned into the wind, deploy rudder against the wind: wind from the left, tail is pushed to the right, nose turns left, rudder right.

How much is enough? In the beginning, the easiest way to tell is by flying the model right at you or away from you while observing the background landscape: If the airplane drifts in respect to the landscape, you haven’t countered the crosswind perfectly. The aircraft will face sideways, depending on the wind strength.

You can quickly get a feeling for the necessary rudder actions by flying to and fro repeatedly. Then you can try flying the aircraft in parallel to your side of view, like in a pattern curcuit. Step by step you will improve your spatial awareness and on top of that, learn how to use environmental landmarks to determine distance and position.